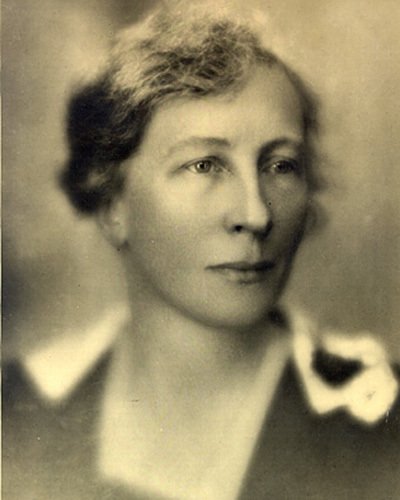

Lillian Gilbreth born Lillie Evelyn Moller in California, was a pioneer in the early 20th-century scientific management movement and helped introduce the field of industrial/organizational psychology to American industry.

In 1900, at her graduation from U.C. Berkeley with a degree in literature, she became the first woman to give the university’s commencement address. Two years later, she earned a master’s degree in literature from Berkeley and had just begun her doctoral studies there, when she met construction company owner Frank Gilbreth. They were married in 1904, and six years later, moved their family, which then included four children, to Rhode Island. The Gilbreths eventually had 12 children, (and often tested their nascent time-management theories on their family.)

In 1915, Lillian received her doctorate in psychology from Brown University. Her change in fields was supported by Frank, who had become increasingly interested in efficiency models for human behavior. Lillian and Frank were equal partners at home as well as in the firm they founded, Gilbreth Incorporated, where they built on the work of Frederick Taylor in the emerging field of scientific management. When Frank died suddenly on his way to a lecture in 1924, Lillian arranged for childcare and delivered his lecture herself. In the wake of her husband’s death, Lillian gave scientific management workshops from home, which eventually led to her position as a highly sought-after consultant to companies such as Macy’s, Johnson & Johnson, and General Electric. Her expertise was also in demand at universities, including Purdue, the Newark College of Engineering, the University of Wisconsin, Bryn Mawr, and Rutgers University, where she taught scientific management. The U.S. government sought her expertise during and after World War II and the Korean War.

At the age of 86, she became a resident lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In addition to many contributions to her field, she is also remembered for the book two of her children wrote, Cheaper by the Dozen, about their unconventional upbringing, which was also turned into several films. She was the recipient of 23 honorary degrees, was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering, and has her portrait hanging in the National Portrait Gallery.

Wilma Mankiller was a social worker, activist, and the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, the second largest tribe in the United States. Born in Oklahoma, her family moved to San Francisco when she was 11, as part of a Native American urbanization program.

Her activism was awakened in 1969, when Native American students gained control of Alcatraz prison in the San Francisco Bay. Following a divorce in 1977, she moved her family back to the Cherokee reservation in Oklahoma and became the economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation. She later began community self-help projects, where she applied for federal grants to improve dangerous, substandard housing as well as repair the water system in Bell, OK.

Her community work was nationally recognized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development for the Cherokee nation, which led to her election in 1983 as Deputy Principal Chief and in 1985, she became the Principal Chief, a position she held until 1995. She was surprised by the fierce sexism she encountered in this matrilineal society, but she remained dedicated to health care, education, job training, creating revenue, and self-governance, working tirelessly to improve the lives and image of Native Americans.

Despite living with several chronic diseases, including cancer and myasthenia gravis, her leadership of the Cherokee Nation was marked by significant improvements for her people. In 1998, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

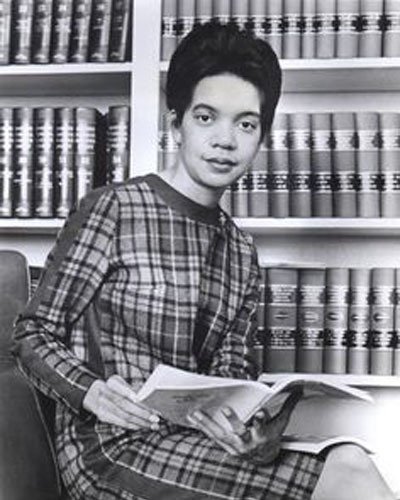

Marian Wright Edelman, an internationally recognized advocate for disadvantaged children, was born in 1939 in South Carolina. Her father was a Baptist minister, who taught her to prize education. A gifted student, Marian studied at the Sorbonne and the University of Geneva, graduated as valedictorian of Spellman College, and was a John Hay Whitney Fellow at Yale Law School. In 1968, she moved to Washington, DC to become counsel to the Poor People’s Campaign, which the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference created to bring economic and social justice to America’s poor.

In 1973, Edelman founded the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), a nonprofit that focuses on child advocacy and research. (One of her first hires was a young lawyer named Hillary Rodham.) Edelman has dedicated her life to finding solutions for children in need.

She has served on the Board of Trustees at Spelman College and became the first alumna elected as a member of the Yale University Corporation. Among her numerous awards and honors are the Albert Schweitzer Humanitarian Prize, the Heinz Award, a MacArthur Foundation Prize Fellowship, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Katharine Graham was born Katharine Meyer in New York City to a former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Eugene Meyer, who purchased the dying Washington Post in 1933. In the summers between college, she worked for the Post, and after graduation, became a reporter for the San Francisco News. In 1939, she joined the staff of the Post, but left during WWII to be with her husband, Philip Graham, during his military assignments in World War II.

In 1945, her father sold the Post to Katharine and Philip for one dollar. Philip became the publisher, expanding the newspaper, purchasing the Washington Times Herald and Newsweek magazine, and moving into television, radio and international news service. After his suicide in 1963, Katharine reluctantly agreed to become president of the company and began to make her mark, bringing in noted journalists to improve the quality of the paper’s writing. Katharine’s public actions coincided with her personal transformation as she moved from being a generally shy, diffident woman, whose life had revolved around her domestic obligations, into a leader who made a tremendous difference in American journalism.

In 1973, under her leadership, the Post published the Pentagon Papers, revealing the extraordinary history and extent of America’s involvement in Vietnam. This act became the basis for the historic U.S. Supreme Court decision in favor of freedom of the press. The Post was also the most important force in breaking the story of the Watergate scandal, which resulted in the resignation of President Richard Nixon in August 1974. Under Graham’s leadership, the news organization thrived economically, culturally, and technologically, becoming one of the top papers in the country. Hailed as the most powerful woman in publishing, she also won the Pulitzer Prize for her 1997 memoir, Personal Story.

Annie Turnbo Malone was an inventor, businesswoman, and philanthropist. Born in Illinois to a father, who fought in the Union Army and a mother who had escaped from slavery, she was orphaned at an early age. Her education, which was cut short by illness, was marked by a profound interest in chemistry. As a teen, she tried her homemade hair products on her sister, eventually creating a non-damaging hair straightener, which she sold door-to-door. In 1902, she moved to St. Louis and started hiring saleswomen, including laundress Sara Breedlove Davis, who would come to be known as Madam CJ Walker. When Walker started her own beauty business, Malone took out a copyright on her formula as well as newspaper ads warning about imitators.

In 1910, Malone opened a manufacturing plant that included one of America’s first beauty colleges. Between the plant, college, and franchises, Malone employed almost 75,000 women. By the 1920s she became a multi-millionaire and was a generous donor to local orphanages, the YMCA, and Howard University.

While a much-publicized divorce and the Great Depression diminished her wealth, her business continued to thrive until the end of her life.

Madam CJ Walker was an entrepreneur, philanthropist, and civil rights activist. When she died in 1919, she was the wealthiest African-American self-made businesswoman in history. Born Sarah Breedlove to parents who had been enslaved, she had only three months of formal education and was married at 14.

After moving to St. Louis with her only child, she started selling hair-care products for entrepreneur Annie Turnbo Malone. Eventually, Walker created her own line of products for black hair and traveled the nation to demonstrate and sell her merchandise. She also built a company that was dedicated to the social and economic advancement of hundreds of African-American saleswomen.

She was a contributor to the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic, cultural, and social expansion in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, and gave generously to causes such as the NAACP and the YMCA. Until her passing at the age of 51, she was active in social and political movements to bring more justice to African-Americans and to women.

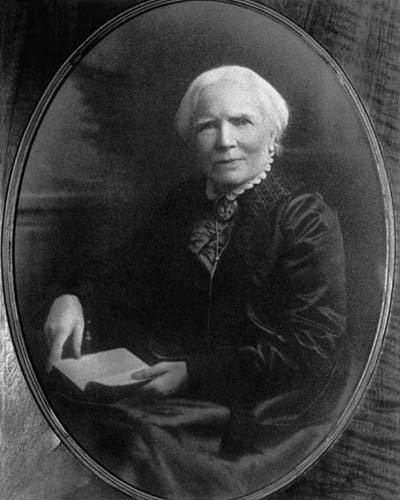

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to be awarded an American medical degree in 1849, when she graduated from Geneva Medical College in Geneva, NY. Undaunted by naysayers, she applied to most of the medical schools in the Northeast and was admitted when the all-male student body voted to let her in as a joke. Turned away from opportunities to practice medicine after graduation, she and a fellow female physician founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, which later added a medical school for women doctors. A lifelong abolitionist and supporter of women’s rights, she campaigned for women’s suffrage.

Esteé Lauder was born Josephine Esther Mentzer in Queens, NY to Hungarian and Czech Jewish immigrants. She began demonstrating and selling beauty products created by her uncle, Dr. John Schotz, after graduating from high school. In 1946, she started her own cosmetics company and her innovative marketing strategies, including “gift with purchase” and counter demonstrations, helped make her not only an extremely successful entrepreneur, but also a role model for thousands of women interested in building a life of impact and authority.