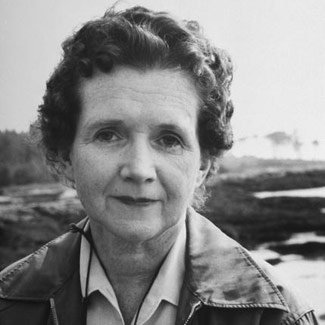

Rachel Carson author, marine biologist, and conservationist, was born on a farm near Pittsburgh in Western Pennsylvania. She began writing stories when she was eight years old and during her college years, contributed to the school’s newspaper and literary supplement. In 1928, after graduating magna cum laude from the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University), Carson pursued a graduate degree at Johns Hopkins University. A few years later, she received a master’s in zoology, but her plans to pursue a doctorate were put aside in order to find work that would support her family financially during the Depression. After her father died in 1935, she assumed responsibility for her mother, sister and her sister’s two children. In 1937, her sister died, leaving Carson the only means of support for her mother and nieces.

Meanwhile, Carson’s career was gathering steam. A temporary job writing radio copy for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries led to a permanent position as a junior aquatic biologist. While in this job, Carson wrote a variety of publications for the Bureau, as well as articles for newspapers and national magazines. In the late 1930s, one of her essays caught the attention of an editor at Simon & Schuster, who asked her to expand it into the book that was published in 1941 as Under the Sea Wind. In the late 1940s, Carson began work on her second book The Sea Around Us, an examination of the science and poetry of the sea, which was published in 1951. It quickly became – and remained – a New York Times bestseller. It also won the National Book Award for nonfiction, received many literary and scientific accolades, and made Carson a nationally known author. Thanks to royalties from the book, Carson was able to leave her job with the government and begin work on her third book –The Edge of the Sea- about coastal ecosystems, published in 1955.

Two years later, one of her nieces died, leaving a 5-year-old son. Carson adopted him and took on his care, along with that of her aging mother. During this time, she became interested in the controversy surrounding DDT and other synthetic pesticides and began investigating this issue. For the next three years, she threw herself into trying to understand the effects of pesticides on humans, wildlife, and the broader natural world. Midway through her work, she was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer, but resolved to try to outrun the clock and finish her book.

She completed Silent Spring in early 1962, and it was serialized that summer in The New Yorker. The book was published later in September. Its urgent message that the deadly effects of synthetic pesticides in the environment and the unchecked damage being wrought in the name of progress created a firestorm of widespread interest and controversy. Despite harsh criticism from supporters of DDT and other pesticides, Carson’s findings and the call to action that these findings presented to all Americans exerted enormous positive impact. In late 1962, President John F. Kennedy asked Congress to study pesticides and created the Science Advisory Committee. This legislative work, combined with citizen activism, resulted in new government regulations to limit specific pesticides’ damage to the environment, including the prohibition of the manufacture, sale, or distribution of DDT. A host of other actions followed, including Earth Day, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Virtually all of the important building blocks of today’s environmental movement are traced directly to Carson’s work. Leaders, such as Al Gore and Bill McKibben, attribute their activism directly to her leadership.

Tragically, Carson didn’t live to witness the worldwide impact of her work. She died of complications of cancer on April 14, 1964 in Silver Spring, Maryland at the age of 56.

Josephine Beall Wilson Bruce was an accomplished linguist, teacher, and activist. She became a renowned social hostess during her marriage to U.S. Sen. Blanche K. Bruce (R-MS), the second African-American senator and the first to serve a full term. A charter member of the Colored Women’s League of Washington, DC, she became the first vice president of the National Association of Colored Women, when it was formed in 1896. She was the first black teacher in the public school system in Cleveland and became the dean of women at the Tuskegee Institute, as well as a writer and successful businesswoman.

Mary Church Terrell was born to enslaved parents; her father, real estate developer Robert Reed Church, was considered to be the South’s first African-American millionaire. Terrell was one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree, receiving her bachelor’s and master’s from Oberlin College.

She taught at Wilberforce College in Ohio and then at the country’s first African-American high school in Washington, DC, where she became the first African-American woman to be appointed to the school board of a major city. She was the first president of the National Association of Colored Women of which she was also a co-founder. She was a member of National Woman Suffrage Association and participated in some of their most notable protest demonstrations.

She went on to co-found the NAACP and what would become the National Association of University Women. After women received the vote in 1920, she continued as an activist for civil rights, standing on picket lines until she was 80.

Frances Perkins was the first female—and longest serving—U.S. Secretary of Labor, as well as the first female cabinet member, architect of the New Deal and the Fair Labor Standards Act, a suffragist, early feminist, and a lifelong activist for the rights of working people.

She was born Fannie Coralie Perkins in Boston and attended Mount Holyoke University, majoring in chemistry and physics. It was a class in American economic history that she took in her senior year that sowed the seeds of activism for labor reform, after the students observed the working conditions in the textile mills along the Connecticut River.

After her graduation in 1902, Perkins taught school in Chicago and converted to the Episcopal Church, changing her name to Frances. In her spare time, she volunteered at immigrant settlement houses and assisted social work pioneer Jane Addams. In 1907, Perkins accepted a position as general secretary of the Philadelphia Research and Protective Association, founded to prevent immigrant girls and young black women migrating from the South from being forced into prostitution. In 1910, she earned her masters degree in political science from Columbia University. That same year, she became the executive secretary of New York Consumer’s League, lobbying for labor reforms in the state capital in Albany, where she made lifelong political allies.

In 1911, she was having tea with friends, when she heard fire engines racing to what would become known as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Perkins witnessed 47 young women jumping to their deaths to escape the blaze in a Greenwich Village factory; she would later say that was “the day the New Deal was born.” After the fire, former President Theodore Roosevelt recommended her as executive secretary to the newly formed Committee on Safety of the City of New York, where she was subsequently appointed to the Factory Investigating Commission. The Commission was instrumental in creating comprehensive reforms in workplace health and safety and toward this end, became a national model. When Al Smith was elected governor of New York, he appointed Perkins to the New York State Industrial Commission, making her the first woman with an administrative position in the state’s government and the highest-paid woman ever to hold public office. In 1928, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected governor and offered her the position of New York Industrial Commissioner, charged with helping find ways to battle rising unemployment. Thanks to her urging, Roosevelt became the first public official to support unemployment insurance.

In 1933, newly elected President Roosevelt asked Perkins to serve as Secretary of Labor. Once sworn in, she worked on reforms such as the minimum wage, the 40-hour workweek, and an end to child labor. She also became the first woman in the presidential line of succession. Almost immediately, Perkins began championing programs for the unemployed, including the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and the Special Board for Public Works. In 1934, she was appointed head of the Committee on Economic Security and in 1935, the Social Security Act was signed into law. Three years later, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a minimum wage, set a legal limit on working hours, and abolished child labor.

During World War II, Perkins used all the tools at her disposal to issue visitor visas to Jewish refugees and expedite their entrance to the United States. FDR’s successor, Harry S. Truman, appointed her to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, a post she held until 1953, when she left for public speaking, writing, and teaching at the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University.

Toni Morrison was an author, editor, teacher, professor, and a defining voice of the African-American experience, who received almost every major literary accolade. She was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, to George Wofford, a welder, and Ramah Willis Wofford, a domestic worker. In 1953, Morrison received a B.A. in English from Howard University, and, in 1955, a master’s degree from Cornell University. She began her teaching career at Texas Southern University, and, in 1957, she began teaching at her alma mater, Howard University. She was married to architect Harold Morrison from 1958 to 1964, and they had two sons.

In 1965, she took a job with L.W. Singer, the textbook imprint of Random House in Syracuse, N.Y., transferring to the publisher’s New York City offices two years later, and becoming the fiction department’s first African-American female senior editor. In that capacity, Morrison championed bringing black literature and authors into the mainstream. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye, which she developed from a short story, was published in 1970. As a single mother raising two sons, she rose at 4 a.m. to work on the manuscript.

Her 1973 novel, Sula, was nominated for the National Book Award, and her third, Song of Solomon, won the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award. Her first play, Dreaming Emmett, about the brutal murder of African-American teenager Emmett Till, was performed in 1986. The following year, she published Beloved, the first novel of what would become a trilogy. The book spent 25 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. The second novel in the trilogy, Jazz, was published in 1992, the same year that her first book of literary criticism, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, was also released.

The following year, she became the first black woman from any nation to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1996, the National Endowment for the Humanities distinguished her with the Jefferson Lecture, the federal government’s highest intellectual honor; her lecture topic was “The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations.” The same year, she received the National Book Foundation’s Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters; in 1997, she released Paradise, the third novel in her trilogy. The first book in the trilogy, Beloved, became a motion picture in 1998.

In addition to continuing to teach and hold chairs at various universities, Morrison wrote a libretto for the opera, Margaret Garner, based on the real-life inspiration for Beloved and wrote a children’s book, Remember, based on the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools. In 2005, The New York Times Book Review named Beloved the best work of American fiction in the last 25 years. Three years later, her next novel, A Mercy, was published. She wrote several children’s books with her late son, Slade Morrison, and, in 2011, collaborated on the opera, Desdemona, a retelling of Shakespeare’s play, Othello, from the point of view of his wife and her African nursemaid. The novel, Home, was released in 2012; that same year, President Barack Obama presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her last novel, God Help the Child, was published in 2015. In the wake of her death, the world mourned the loss of a major intellectual force and a preeminent voice for the African-American experience.

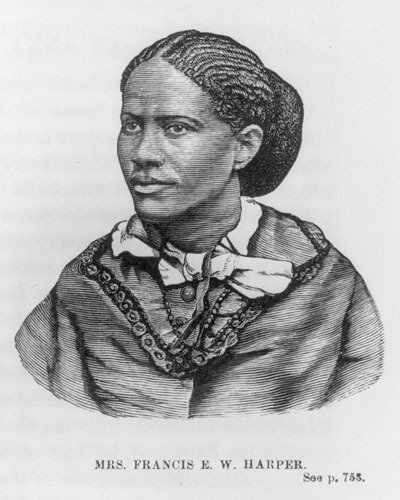

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a poet, abolitionist, author, orator, and social reformer, who was dedicated to women’s suffrage, abolition, and temperance. Born free, she became a teacher and published poet. She lectured throughout the East and Midwest on the need for education for African-Americans and became the director of the American Association of Colored Youth in 1894 and vice president and co-organizer of the National Association of Colored Women in 1897.

Gloria Steinem, a journalist, author, public speaker, and influential activist in the feminist movement, was born in 1934 in Toledo, Ohio. Her parents divorced when she was 10 and she was left to take care of her mentally ill mother. In 1956, she graduated magna cum laude from Smith College and earned the Chester Bowles Fellowship, which allowed her to spend two years studying in India. This experience planted the seeds for her later activism.

Steinem initially pursued a career in journalism, although most of her assignments were for what were called at the time “the women’s pages.” Her undercover exposé of working conditions at the New York City Playboy Club in 1963 catapulted her into the national spotlight. In 1968, she became a co-founder and editor for New York magazine.

Her coverage of the women’s liberation movement led to a 1969 event to promote abortion rights in New York, where she publicly shared her own abortion experience. It was the beginning of her involvement in the women’s rights movement and her recognition as a national spokeswoman for the cause.

Following the 1970 takeover of Ladies Home Journal by women’s rights activists protesting the lack of coverage for the movement, Steinem was inspired to start Ms. magazine. Almost 50 years later, the publication remains the standard for reporting on feminist issues.

In addition to her writing, editing, and public speaking, Steinem co-founded a number of important progressive women’s organizations including, the National Women’s Political Caucus, the Women’s Action Alliance for children’s education, the Women’s Media Center, Voters for Choice, and the Ms. Foundation for Women. She also helped establish Take Our Daughters to Work Day. The author of eight books, Steinem is the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom; Rutgers University created The Gloria Steinem Endowed Chair in Media, Culture, and Feminist Studies in her honor.

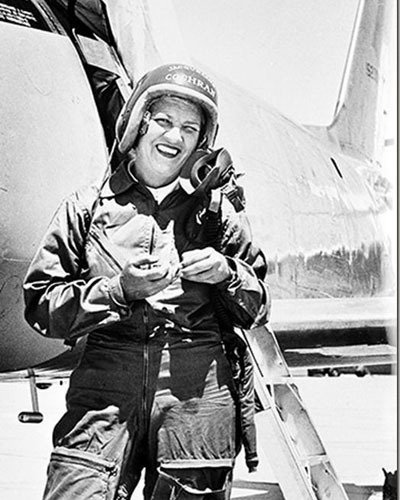

Jacqueline Cochran born Bessie Lee Pittman in the Florida Panhandle, holds more aviation distance and speed records than any pilot in history. She married Robert Cochran in 1920 and when the marriage ended, she became a hairdresser and eventually moved to New York City. She worked her way up to the prestigious salon at Saks Fifth Avenue and with the help of her second husband, Floyd Bostwick Odlum, started her own successful cosmetics business.

After a friend offered her a ride in an airplane, she began taking flying lessons and within two years, obtained a commercial pilot’s license. She soon joined female aviators of the day in competition, and worked with Amelia Earhart to open the prestigious, cross-country flying Bendix Race to women. In 1938, she won the Bendix trophy, set new speed and altitude records, and was acclaimed as the best female pilot in the United States.

Before the United States entered World War II, she joined the “Wings for Britain” program to ferry aircraft to England for defense and became the first woman to fly a bomber across the Atlantic. She volunteered for the Royal Air Force and spent the next several years working on recruiting qualified female pilots from America. In 1939, she began urging people in authority, including Eleanor Roosevelt, to support women pilots assuming non-combat aviation jobs to free male pilots for active duty. In 1943, after years of lobbying, the Women Airforce Service Pilots was created with Cochran as director. She supervised training for hundreds of female pilots between 1943 and 1944 and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, the highest non-combat award in the U.S.

In 1948, Cochran joined the Air Force Reserve as a lieutenant colonel, retiring as a full colonel in 1970, having been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross three times. She set numerous aviation firsts for women, including breaking the sound barrier while setting the world speed record, landing and taking off from an aircraft carrier, flying jet aircraft during a transatlantic flight and flying fixed-wing jet aircraft.

In 1956, Cochran ran for Congress in California’s 29th District on the Republican ticket, narrowly losing to America’s first Asian-American representative, Dalip Singh Saund. While never as famous as her friend Amelia Earhart, Cochran was inducted into several halls of fame, had a California airport renamed in her honor, and, in 1953 and 1954, the Associated Press named her Woman of the Year in Business.